the first memory

“Responsibilities” Fulfilled by the Top Runner

22 April 2024

On March 31, 2023, JERA decommissioned the Kashima Thermal Power Station Units 1 through 6 (total 4400MW), which had been in a long-term planned shutdown. The demolition work will continue for many years.

The Kashima Thermal Power Station Units 1-6, which supported Japan’s economic growth and regional development, have fulfilled their role and brought down the curtain on their history. In fact, this project has a significant meaning more than that.

One is that it will be the Japan’s largest demolition project in terms of scale and duration. Another point is that since JERA was established, this is the first demolition project JERA has worked on consistently from planning to completion. Also it will take a role to take over the efforts to other power stations demolition projects to be followed.

This article is the first of three parts that follow the ending of the Kashima Thermal Power Station Units 1through 6. We interviewed to Hideaki Takayasu, General Manager of Kashima Thermal Power Station about the history of the power station, the background led up to the demolition work, and the goal of this project.

INDEX

50 Years of History Together with the Local Community

The chimney, one of the tallest in Japan (230m) will also be removed.

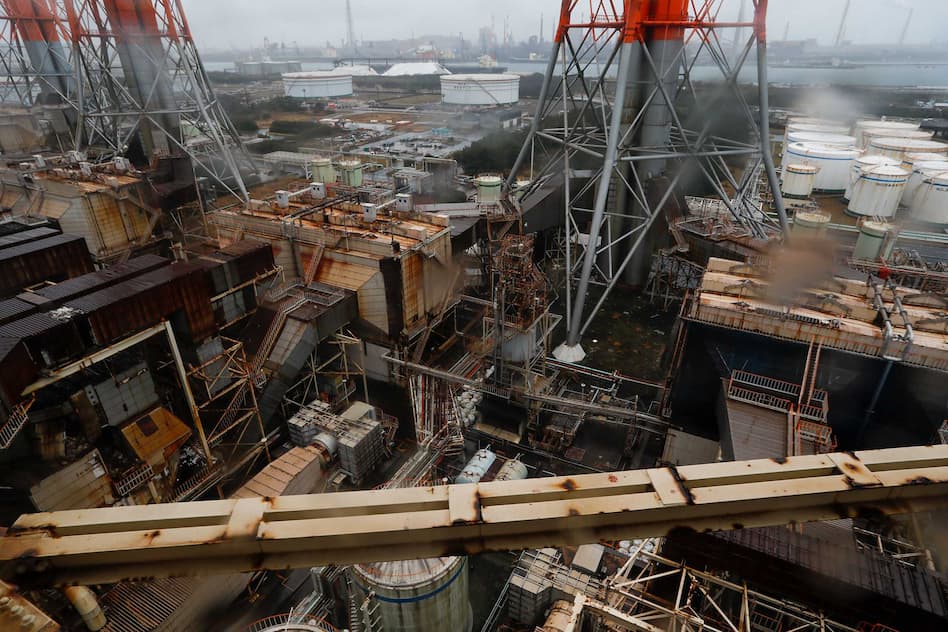

On the day we visited for the interview, the weather was bad with heavy rain and howling winds. Three symbolic chimneys and gigantic power generation facilities appeared in the view where splashes large droplets of rain which will turn into hail.

At first glance, power generation facilities looks sturdy. But as a result of no one entered the facilities so many years due to its long-term planned shutdown, rusts and damages can be seen everywhere and the facilities support its decaying body in the harsh environment. Its appearance makes us feel the weight of history which has supported a stable supply of energy.

Equipment is damaged due to corrosion.

The Kashima Thermal Power Station is located in the Kashima Coastal Industrial Zone, the largest in Ibaraki Prefecture, with approximately 180 companies and over 20,000 employees. Originally, this area was a vast area of sand dunes but the governor of Ibaraki Prefecture began development in the 1960s. Construction of the Kashima Thermal Power Station began in 1968. Since the first unit started operation in 1971, JERA has consistently adhered to the principles of “cooperation with the local community and environmental protection”.

“The history of this power station will not have begun without the local people who gave us the land, and we have been supported by the local community until today. We feel a deep sense of gratitude”.

Hideaki Takayasu, General Manager of the Kashima Thermal Power Station

His hometown is Kashima city and he decided to work for the Kashima Thermal Power Station when he visited the power station.

So said Hideaki Takayasu.

At its peak, over 300 employees and over 500 employees from partner companies were working at there. Now that demolition work has begun, 66 employees remain the site. Times have changed, role have changed and systems have changed. However, we keep the attitude to commit to coexisting with the local community and prioritizing safety as a top even in the phase of demolition work.

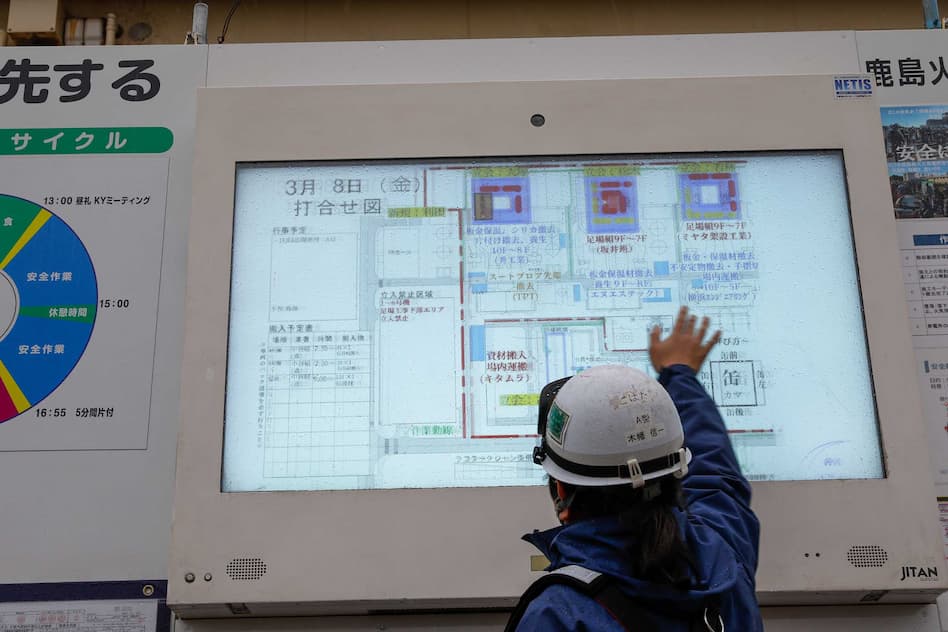

In collaboration with partner companies, “visualizing” when, where and what construction is progressing.

With the exception of the Unit 7 that was installed after the Great East Japan Earthquake, the Kashima Thermal Power Station is now quietly bringing down the curtain on their history. Now the decommission of the power station has been decided and demolition work is progressing, we asked Takayasu about his feelings.

The Power of the On-site that Has Overcome Numerous Hardship

From the upper floor of the power station. Now it doesn’t make any noise and quietly stands.

If we look at the history of the Kashima Thermal Power Station, evidence that it has always taken on new challenges to adopt needs of the times is unveiled.

“For example, we introduced DSS (Daily Start Stop) for large capacity once-through boilers. To put it simply, Unit 1 has a maximum output of 600MW and it had continued to operate at maximum output for 365 days a year. In order to use electricity stably, power consumption (demand) and power generation (supply) must always match exactly, but due to the expansion of other power station, the Kashima Thermal Station was required the function to adjust the supply capacity according to the electricity demand, and to meet those requirements, we frequently carried out modification works to increase or decrease the power output.”

On the other hand, if you shutdown or startup the generator itself rather than increasing or decreasing the power output, the cost for fuel and water will be incurred. Therefore, in order to reduce the minimum output, we utilized the equipment knowledge and experiences of the power stations employees to review the minimum output and conduct the modification of boiler by changing the voltage. In other words, by modifying to continue generating electricity at the minimum output during the night time when the electricity demand is low, frequent startup/shutdown became unnecessary. In this way, the Kashima Thermal Power Station has constantly transformed in response to needs.

What to do in order to supply energy continuously? Much of this trial and error was born out of ideas from the on-site, including employees, partner companies, and manufacturers.

“Of course, upper management decides on major policies, but top-down approaches tend to make the content qualitative and abstract. In order to make appropriate modification in response to the times and power station, ideas from the on-site is essential. When I was working at Tokyo Electric Power Company, I was in a department that was responsible for maintaining thermal power generation equipments at the head office, and I found that suggestions from the on-site are extremely important even at the phase of considering what modification should be made.”

We eliminate barriers, exchange opinions, and turn ideas into reality. This culture was also utilized during the Great East Japan Earthquake. Units 1 through 6 suffered severe damage from the tsunami and liquefaction. However, all units 1through 6 were restored about two months by restoration work day and night.

“It was a heroic effort to restore six power generation facilities in two months despite the severe damage caused by the tsunami and liquefaction. This achievement was because employees, partner companies, and manufacturer united and made efforts together for restoration. At that time, it was actually visible that the area of rolling blackouts in the Tokyo metropolitan was being reduced with each unit was restored, and I heard this gave them motivation for the restoration work.”

The Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011. The moment when the tsunami hit the water outlet channel in the power station.

A Difficult Decision Because We Have Adapted to the Times

Various safety measures have been taken within the facility, including securing passageways to ensure safe work.

In the 1960s, when the Kashima Thermal Power Station was built, oil was the main fuel for power generation, but gradually LNG (liquid natural gas), which emits less CO2, has become popular. Furthermore, the mainstream method of power generation has shifted from “steam power generation” which generate steam by burning fuel in a boiler, to “combined-cycle power generation”, which improves efficiency by combining the gas turbine and the steam turbine. As a result, the role of unit 1through 6, which generate oil-fired steam power, gradually diminished.

“Initially, operations were stopped on a daily basis, but gradually stopped on a weekly and even monthly basis. Under these situations, in 2014, long-term planned shutdown were implemented for Unit 3 and 4 in April, Unit 1 in September, Unit 2 in October, and Unit 5 and 6 in April 2020.

The next issue was “deterioration with age”. Just like house, equipments that is no longer used were deteriorated day by day. Further, due to the location facing the sea, equipments were getting suffered from salt damage and corrosion harder. Given the situation, there were voices for equipments to be removed immediately, but due to the impact of electricity demand after the Great East Japan Earthquake, it was not possible to proceed with the plan and implementation of the demolition.

“ Although safety measures such as regular maintenance were taken, the equipment deteriorated faster than expected, and in the meantime, the equipment was rotting away. When it was finally the time to carry out the demolition project, there was the issue that “is it safe to get in the facility?”. It was impossible to make a judgement because no one had entered the facilities due to the long-term shutdown. However, because we can only move forward after understanding the on-site, actual situation and reality, knowing the current situation, and improving the work environment, I made up my mind to start investigation”.

The investigation was conducted over one and a half months from July 2023, with employees taking a central role. This was a steady work to check stairs, floors and ladders etc. which will be used during the demolition work process one by one by hitting with a hammer. We made it our mission to inform our partner companies of all dangerous areas, and after moving forward one by one, we were finally ready to begin full-scale demolition work.

Inspection work with a hammer. The sound is said to be different in areas with severe damage.

“In the beginning, even the employees were worried about the investigation. We were not sure what kind of investigation method would be the best, so we did a lot of trial and error, and gradually we were able to hold the key points. This is how we finally investigated the whole facilities. Now we have confirmed the entire situation, we are currently proceeding with the removal of the severely damaged boiler heat insulation equipment and smoke duct equipment. Following this, we plan to remove the fuel tank in parallel.”

As an Evangelist for Demolition Work

Power station employees and Takayasu. Currently, four teams of four people, including the operation unit manager, are monitoring power station around the clock.

JERA is also considering the removal of deteriorating power stations, after the Kashima Thermal Power Station Units 1through 6. In other words, the Kashima Thermal Power Station is the first group to be demolished and the work carried out here will also affect other power stations.

“For example, in order to carry out demolition work, we need to apply to the relevant authorities in advance. Since we are a top runner, we have to compile such administrative works into a database so that it can be shared with other power stations. It is also important to disseminate within the company the points that need to be considered in order to carry out demolition work that give top priority to safety. We use the company newsletter and internal SNS to frequently communicate our efforts. This project also incorporates information sharing as a necessary process.”

To set a precedent as a top runner, what is needed is the power of the on-site, which has been continued to be the driving force. “We need employees with a variety knowledge such as employees who are well-versed about this power statioin, employees who can maintain boilers, and also employees who are proficient in turbines,” says Takayasu. Each of them utilizes their specialties and eventually develops into professionals in demolition work. In fact, this is another aim of this project.

“As time goes by, there will continue to be power stations that will be demolished after their role has been completed. It is expected that employees who work on this demolition project will play active role as “evangelist” at other power stations planned demolition after finishing their work at the Kashima Thermal Station. The employees involved in this demolition project will increase their own value through their experiences here and spread their wings soar high. When we can achieve this, I believe this project will truly reach its goal.”

The Kashima Thermal Power Station Units 1through 6 is about to bring down the curtain on its history of over 50 years. How can we finish in a way that will be remembered for future generation? That challenge has just begun.

(To be continued)

RELATED STORIES

Front Lines of Thermal Power Generation Where Electricity Is Born for Our Everyday Life.

Drawing with the Students of Futaba Future School! Hirono Thermal Power Station Mural Art Project Part 1