Where the Creativity of Business Meets Art Second Interview: Education x Creativity (Part 2)

7 July 2023

Recently, I've developed a new presentation style, where I seek to connect with the audience by openly sharing my weaknesses (Miwa)

Miwa: This may sound self-indulgent, but I've recently grown to love giving presentations. So much that you might even call it a hobby. I started participating in startup pitch competitions and even came in second place a few times. I was struggling with why I could never seem to win first place when there was a terrorist attack in Bangladesh. I fell ill both mentally and physically and had to take two months off work to recover. But about three months later, I won a presentation competition for the first time in my life, which was the catalyst for the publication of my book, Compassion Presentation. It was at that time that I started developing a new style of presentation where I laid my weaknesses bare, including my past experiences with failure. I believe presentations are one of the best tools entrepreneurs and business managers have to express themselves, one where they can share all aspects of their lives. In my book, I write about how we should create a world where it’s okay to be less than perfect instead of always having to strive for perfection. I feel that it’s not my weaknesses, but rather, what I've gained from the culmination of my failures that have given me a way to overcome obstacles, and in that regard, I've come to believe that there may not be much difference between a performance in the world of art and a presentation in the world of business and NPOs.

The act of empathy is very similar, whether you're performing music, giving a presentation, or working with someone else. When I sing, it brings me into a state of mindfulness. And being fully present allows the emotions of the song to permeate my whole being, and the music naturally flows through me. This connection between the music and myself enables listeners to empathize with the music by projecting their own emotions and experiences onto it (Tanaka)

Tanaka: The act of empathy, or considering other people's feelings, is always the same, whether you're performing music, giving a presentation, or working with someone else. I believe that music is emotion embodied, and tones are the colors of those emotions. That's why the more emotional richness you have, the more you are able to produce a variety of tones. And the more you can imbue those tones with emotion, the more they will connect on an emotional level with other people. Listening just now, I wondered if, in the business world, the wider the range of emotions you have inside, the easier it is for people to empathize with you and your presentation.

Miwa: I have a vivid memory of the scene inside the venue when I won the presentation competition. Even now, I can clearly picture the audience, many of whom wore expressions similar to mine as I spoke about my difficult experiences in Bangladesh and the pain of parting ways with loved ones. Although the audience hadn't lived through my exact circumstances, the fact that they all shared similar expressions indicated that they had likely encountered similar challenges in their own lives. I could sense a connection between their cherished memories and my own. Despite the challenge of empathizing with the lives of the audience while delivering my presentation, I spoke with the intention of fostering that connection. Now, as I work with teachers who are assisting me with e-Education, I encourage them to communicate with intention when engaging with their students.

Miwa: Ayako, I'm very curious to hear what you think about while you are singing. What’s on your mind in those moments just before you start singing?

Tanaka: I don't think about anything. I try to clear my mind. It’s almost like Zen meditation. Songs are imbued with stories—stories of love, stories of loss, or stories of pure enjoyment or pleasure. If I clear my mind, I can become a conduit for the song's emotions. Even if I haven’t had a similar experience to the one described in the song, clearing my mind allows the feelings of the song to permeate my being and flow through me as music. This connection enables listeners to empathize with the music through their own experiences. Your thoughts on presenting are a lot like music in that way.

I find myself drawn to the people in developing countries because their lives are truly beautiful and full of hope. I think there will come a day when we will learn from them (Miwa)

Miwa: That's a great way to look at it. I find myself drawn to the people in developing countries because of the pure beauty and hope in their lives. That’s why I want more people to attend university, but that's just a start. If more people can express themselves and fulfill their dreams, the whole world will ultimately benefit. I am doing what I do, convinced that there will come a day when we will learn from them. Ayako, you are working to expose young people in Argentina to the joys of music, and there must be a sound unique to them, a rich sound imbued with their lived experiences and personalities. I would love to hear about how the future will be shaped by those children in Argentina after their experiences with music. I would love to hear more about what kind of future you hope to create with the children of Argentina and their experiences coming to Japan.

Working with the National Youth Orchestra of Argentina, our main goal is to use art and music to nurture emotional intelligence, which is fundamental to us as human beings. I also think it's important to fully enjoy both working in step as part of a group and also knowing when it’s okay to express yourself freely as an individual (Tanaka)

Tanaka: Although Argentina is part of the name, the orchestra actually includes children from across South America, including Peru and Venezuela. I think simply being in that environment together allows them to cultivate a range of emotions. The children may not necessarily grow up to be musicians, but what they learn through their musical education can be very useful in other parts of society. Especially in an orchestra, which consists of many members, it's not always easy for children from different countries and backgrounds to work toward the same goal. In these kinds of group activities, we aim for the best outcome from everyone by locking step with one another, supporting each other's strengths and weaknesses through practice, all the while staying true to our original intentions. This kind of learning is different from rote learning and standardized tests at school, and I believe it plays a critical role in brain development. Above all, I think it's essential to nurture a rich emotional intelligence within this framework of art, which is the central theme of the orchestra. I think young people of various backgrounds and family situations learn a lot in the National Youth Orchestra of Argentina, and they can create a sound that is uniquely their own. When some of the children hear a new sound for the first time, they wonder why and start to become aware of the influence of factors such as where they grew up and how they’ve practiced. That, in turn, allows them to be more receptive to different emotions as they arise, which is really a special thing.

Miwa: I imagine that it’s a difficult balance to get everyone on the same page to create a single piece of work as an orchestra.

Tanaka: Well, it's important to fully enjoy both working in step as part of a group and also knowing when it’s okay to express yourself freely as an individual.

Okuda: I'm really curious to hear the National Youth Symphony orchestra "José de San Martín". Japan has a very homogeneous society with generally affluent individuals who come together to form orchestras, play music, and hone their respective skills. The sound produced by this kind of orchestra must be completely different from that of a diverse group of people from different nationalities and backgrounds, like in Argentina. Even a standard performance must sound different, and I'd like to see what kind of exciting things emerge when different kinds of people come together as an orchestra. This aligns with my desire as a business person and manager to create excitement within the company.

Companies can only grow so much by efficiently producing average products. To scale beyond that, they must create breakthrough products that can change the very fabric of society. They need to create something new and unique. You might think energy is all the same, but electricity comes in different forms, all with different values—it can be environmentally friendly and flexible, or it can be just the opposite. As we work to introduce new types of energy and new value into society, there are times when a highly homogeneous organization doesn't work, and as executives, we need to take on the challenge of transforming the company from within.

When someone says, “You’re too early,” I try to take it as a compliment. (Miwa)

Tanaka: I really like Kaito’s story about being “too early.” If someone told me, “You’re too early,” I’m the kind of person who would respond by saying, “Then I’ll be the one to do it, and I'll do it now.” But those words—“you’re too early”—can be a dangerous phrase that can crush someone’s spirit.

Miwa: Let me tell you the story behind “You’re too early.” When we launched e-Education in 2010, Bangladesh was considered one of the poorest countries in the world, with no internet and limited access to electricity. When I expressed a desire to support high school students using cutting-edge technology rather than the primary school support typically provided by JICA and other international organizations, I was repeatedly told by people both locally and in Japan that it was “too early.” Now, I have the honor of advising the Rwandan Ministry of Education, but when I told them I wanted to do the same thing in Rwanda that we did in Bangladesh 10 years ago, they responded, “It’s too late.” The impact of COVID-19 certainly played a role, but when I was told “it's already too late” for something that was “too early” 10 years ago, I realized that there was a lesson to be learned.

Tanaka: Do you still think that it was too early then, even now?

Miwa: I think saying it's "too early" to do something means that someone will eventually do it someday. And if someone is going to do it eventually, then maybe I should be the first. So even if I could go back ten years, I don’t think I would do anything differently. When someone tells me, "You're too early," I try to take it as a compliment. I remain unfazed and carry on doing whatever it is I'm doing.

Okuda: Taking "too early" as a compliment, that's very good.

Miwa: In the Japanese sense, “it's too early” might sound like a phrase to stop, scold, or mock someone. But in 2017, when I went to San Francisco and Silicon Valley and shared my story, people would clap their hands and say, "Wow! You’re too early!!," which was obviously a compliment. At that moment, I took my foot off the brakes in my head and decided then and there to never use them again.

Despite the various ways that technological progress brings about growth and development, I think we naturally tend to think about things based on a country’s growth pattern, which leads to the phrase “it’s too early” (Okuda)

Okuda: I think having a positive attitude is important, just like how you used the term "unusual" as a compliment. People who don't use “too early” in a positive sense are those who can only think about things based on their own experiences. In other words, some people may think that because Japan has developed in specific ways, that progression is the norm for growth. And by that token, because Bangladesh hasn't achieved the same amount of growth, they deem it to be “too early.” One of my favorite quotes is attributed to Einstein: “Common sense is the collection of prejudices acquired by age eighteen.” After all, what we see as common sense is the common sense built up in the history of the small island country of Japan. When we look at the world, we see there are any number of ways for a country to develop. Take people who have grown up using the internet and people like me who remember when there were only rotary dial phones. We are at entirely different stages of development. Japan’s record period of economic growth started with the construction of expressways and the Shinkansen, which was followed by the building of large-scale power plants, power lines, and then telephone poles to bring electricity and telephone lines to cities across the country. This is how Japan’s social infrastructure was built, and from there, new industries were born. But now we have wireless connectivity, so we don't need to erect telephone poles and run telephone lines. With electricity, too, before covering a country with power lines, we should aim for a certain degree of local production and consumption and generate electricity with resources available in that region. We can use batteries to cover any deficits, and if that's still not enough, we can implement measures like energy conservation. These mindsets help us start living with electricity in new ways.

Despite the various ways technological progress brings about growth and development, I think we naturally tend to think about things based on a country's growth patterns, leading to the phrase "it's too early." It’s the same in life. Those who perceive their accumulated experiences as successful are quick to claim that something new is “too early,” whereas individuals starting from a different standpoint struggle to grasp their viewpoint. I suppose that saying something is too early is a phrase used by people wrapped up in their own common sense.

Right now, everyone in Africa is talking about “leapfrogging.” There's a growing feeling that the continent will jump ahead into the future. (Miwa)

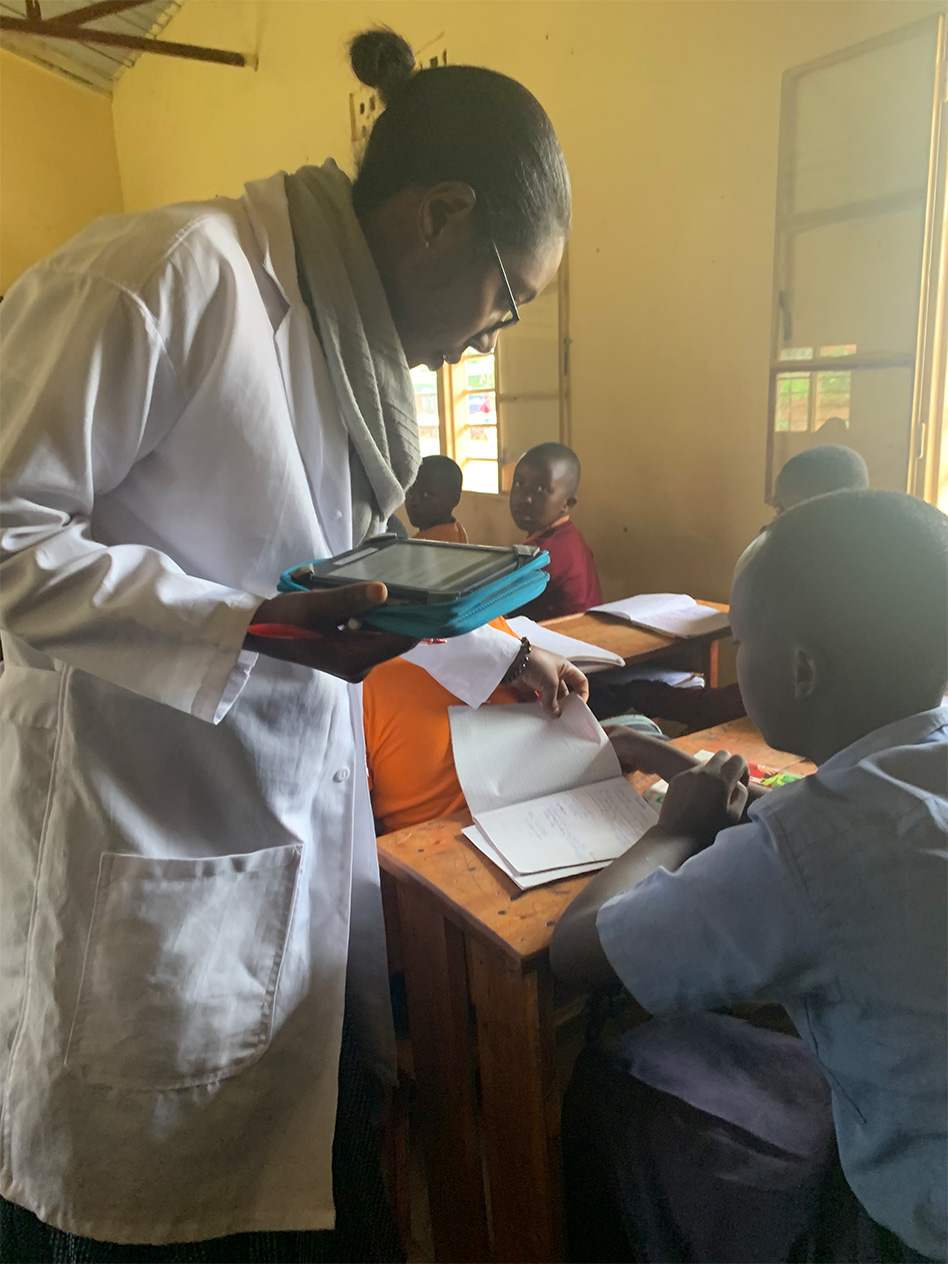

Miwa: Last month, while I was in Rwanda, I kept hearing the phrase “leapfrogging.” The Ministry of Education in Rwanda, as well as high school students, seemed to be using it to describe innovations that have the potential to change the common sense of society in one fell swoop. This leads me to believe that Africa is no longer a backwater but a frontier where innovation will start to emerge. In business terms, it’s like “the seeds of innovation.” It’s about changing the world, and it’s not impossible. They can already envision the future to a certain extent. We just haven’t made it a reality yet.I have a feeling that the country of Rwanda—and the entire continent of Africa—are trying to move in that direction. Today, almost all high school teachers in Africa have their own computers and state-of-the-art tablets. They’re now trying to get devices into the hands of all of their students, and I'm involved in an advisory capacity to help make that a reality. In a country where only one in five people have access to physical textbooks, it's becoming clear that we no longer need them.

Okuda: If they have tablets, they don't need paper, right?

Miwa: Geographically speaking, Rwanda is a small country, surrounded by larger nations and devoid of paper resources. It turns out that distributing tablets is actually cheaper than using paper. So they aren't fantasizing—they genuinely believe in a future where every child will study using a tablet. Yet people from developed countries say that it’s impossible. They’ve recently responded well to this accusation, saying, “Leapfrog is here and now,” which left a strong impression on me.

To understand the value of “leapfrogging,” you need to be able to clear your mind and face the concept head-on. (Okuda)

Okuda: As a business leader, understanding the value of "leapfrogging" is paramount. It's crucial to be able to listen with an open mind when someone explains a new business or innovation. If you can't do that, your company will end up just going around in circles.

Miwa: In the past, innovation was often described as being “disruptive.” People pursued their ideas with force as if running head-first through a wall, and many succeeded. But the innovation that people in Africa are envisioning now is this “leapfrogging,” or jumping over, older technologies. Frogs don't look at the wall when they leap. They just want to go as far as they can, so they jump as far as possible and end up going over the wall. It's almost as if the moment you think there is a wall, you lose the ability to jump. Okuda-san, you mentioned the importance of "clearing your mind," but you also need to have a solid, indestructible foundation built on your experiences and knowledge in art and business. When trying to build upon this foundation, as Ayako said earlier, compartmentalizing it is, in my opinion, a very important aspect of “leapfrogging.”

Okuda: Clearing your mind might be a way of opening yourself back up to new things. Business demands logic. You need a logical explanation backed by numbers when talking to financial institutions that lend money or to investors and other stakeholders. But if you get stuck in that way of thinking, your curiosity for new value wanes. I realize that way of thinking won't change the world, so I have naturally developed the habit of trying to clear my mind when considering an investment proposal, asking myself how it might open up possibilities going forward or how it might help change society if we combine it with other investments. As I was listening to your story, I thought that this might be a similar approach to your ideas on compartmentalization.

Businesses report their activities using financial statements, which they are always trying to improve. If a company has a solid net worth, for example, it is thought to be healthier. But views on this net worth can differ: some see it as acceptable to take risks using the equity, while others insist that you must always make a decent return on your equity. The difference of opinion here is quite significant, and I think it is similar to what we discussed earlier about how you interpret “unusual." Going forward, companies will be responsible for creating new value and ensuring its integration into society, so there is now a demand for businesses to reevaluate their notions of acceptable risk-taking and investment. A change in mindset is critical.

Miwa: I had an opportunity to see what apps high school students in Rwanda have installed on their smartphones. You can imagine that they would have social media apps like Facebook and Instagram installed, but apart from these, the most downloaded apps were ones related to cryptocurrencies. In other words, they are trying to use their phones to make money. The future of cryptocurrencies is still unknown, but still, they may be far ahead of Japanese high school students here. Even though I was trying to look at the children in Rwanda with fresh eyes at the time, I found myself setting a limit for them, almost like a kind of glass ceiling. When I saw high school students trying to make money with just their smartphones, I thought that this might be one form of “leapfrogging.”

What’s more is that it wasn’t something they weren’t putting a lot of effort into. I felt like I was seeing a new world where they were trying to start a business and make money with just a swipe of their finger. In both art and business, I want to see a future where the next generation expresses themselves and creates new businesses in ways we never imagined. I’ve reaffirmed my belief that the power to make this possible lies in an education that believes in “leapfrogging” and communicates this to children.

Okuda: That’s something that people of all generations must strive to understand. We accumulate ideas throughout our lives, and we inevitably make judgments based on them, but I think we are headed for a time that will test our ability to set those experiences aside when trying to open ourselves up to new ideas.

“I find myself in a foreign land.” After working overseas for a decade, I've slowly begun to realize what it means to be Japanese. (Miwa)

Miwa: As someone involved in education, it's truly a blessing to be able to hear directly from the children today. Being in an industry where you have to force yourself to put aside preconceptions, I believe that having opportunities to slowly unravel and compartmentalize my own biases is a precious experience that I've been given precisely because I'm involved in education outside of Japan.

Okuda: I think that is the real pleasure of traveling abroad, which you are unable to understand if you remain in a society as homogeneous as Japan’s. When you explore a new place where both the culture and the level of economic development are so different, you become aware of a completely different set of values. I'm having a similar experience talking with you two right now. I'm doing my best to open myself up to your stories.

Miwa: When I was backpacking, I came across a Chinese proverb that says, “I find myself in a foreign land.” I’ve heard it means that by visiting a foreign country, you get to know yourself for the first time, and after working abroad for more than ten years, I've slowly begun to see what it means to be Japanese. Ayako, there must be a version of Japan that you have come to see now that you’ve spent more time abroad than you have in Japan. Not to mention your opera on Hosokawa Garasha. I think your approach is remarkable, and I'd like to hear how you came up with your ideas and decided to bring them to life.

When I learned that an opera about Hosokawa Garasha had been made in Vienna shortly after her suicide in the 1600s, I felt that I needed to retell her story as a Japanese person (Tanaka)

Tanaka: I have always felt that Japanese culture could be expressed through Western music. Since I specialize in Western music, I’ve always wanted to use it to convey the essence of Japan. That's the first reason. And when Garasha Hosokawa killed herself in the year 1600, the missionaries in Japan relayed the story to the Jesuit church in Vienna, with one priest so impressed by the story that he quickly created an opera with Garasha as the protagonist. The fact that the aristocrats of the time learned about Garasha by watching this opera, which spread throughout Europe, primarily among the nobles of the Habsburg Empire, including Marie Antoinette, is a very interesting part of history. I felt that, as a Japanese person, this story needed to be retold, but I didn't want to recreate the opera as it existed then. I wanted to create something original from scratch, something entirely my own. And I chose Garasha because many aspects of her life are easy for Europeans to empathize with.

Miwa: I've heard that the world’s most fierce competition over entrance exams is in Japan and South Korea, but it wasn’t until I went overseas that I found out that Japan is seen as being obsessed with exams by the rest of the world. The notion that Japan is crazy about exams is becoming a global sentiment, but somehow Japan itself is the only one out of the loop. The only way to recognize things like this is to go abroad. For me, your story about Marie Antoinette learning about Japan through the opera felt similar to how Japan is seen as an exam--obsessed nation.

Okuda: I've only had the opportunity to work overseas once, and I was shocked to find that Japan looks at the world in its own distorted way. I was working in the planning division at the time, with an interest in corporate strategy. I grew up learning that a company's aim is to increase productivity, efficiency, and profits and that the culture of mass production and consumption touted by the United States was the key to success. I thought that was the global standard. Then, I visited a German beer company whose goal was to sell their beer at high prices in a select number of restaurants in developed countries, not to turn it into a mass-market item. They told me their beer was available at certain high-end restaurants and that they commanded high prices and made a profit by branding their product as something exclusive and would never try to make a beer that appealed to the masses. After that, I heard a similar story when I went to a car company in the same city. They said that creating a car loved by 5% of people in countries with a per capita national income of more than $20,000 was necessary to maintain brand value and increase added value. This clearly turned on its head the idea that companies should relentlessly increase productivity and pursue efficiency. I learned for the first time that Europe is trying to establish itself in a different league from the United States because the corporate strategies are so different. It's good to learn strategies from MBA textbooks, but really, you can create whatever strategy you like as long as you have adequate reasoning behind it. But when you're creating a strategy, sensitivity is important, and creativity is essential. It's important to clear your mind and open yourself up to new things, which connects to what I was saying earlier.

Miwa: This also ties back to the story about the orchestra in Argentina, but I think that one way to clear your mind would be akin to using a map to see where you fit into the bigger picture. There’s that sense of Japanese-ness you only realize once you talk to someone who isn’t Japanese. That feeling of pushing the reset button each time I interact with a non-Japanese person is something that never goes away for me.

There has been a significant change in children in Bangladesh, where they used to make up their own toys and games and run around in the rivers and rice fields. There are now one-year-olds whose best friend is YouTube, and they’ve become more passive. (Miwa)

Miwa: I've been feeling a sense of crisis recently. Ten years ago, students in Bangladesh using e-Education had a twinkle in their eyes as they chose what they would learn the next day. They used to run around in the rivers and rice fields, making up their own toys and games. So they would think about tomorrow as a matter of course, but they were masters at enjoying the present. But ten years on, the situation has changed, and an increasing number of children can't think for themselves. I feel like smartphones have had an impact. One of my friends in Bangladesh has a five-year-old whose best friend is YouTube. She’s been exposed to it since she was a baby and knew how to skip ads by the time she was one. From early childhood, children are in a highly stimulative environment where information is all around them. I also think music has become very accessible to them. Maheen's 5-year-old daughter can sing songs in 10 different languages. With YouTube, they’re surrounded by information, so they have the opportunity to encounter lots of different music, which is a good thing, but they are more passive, and I think there are now relatively fewer opportunities for self-expression. Ayako, what kind of education would you want to provide if you were to become a school principal or a music teacher?

Today there are fewer musicians and students who read scores and more who use video platforms and play by ear to copy a recording exactly as they hear it. I don't understand the point in performing that way (Tanaka)

Tanaka: Today, students and professional musicians alike are increasingly learning new pieces without even looking at sheet music. Instead, they listen to recordings online and do note-for-note covers. That kind of performance is nothing but a copy of someone else, and it becomes something devoid of any emotion with no basis in your lived experience. Those who only listen for a moment may not notice, and you might save time preparing for a live performance this way, which itself may go off without a hitch. But if you continue to play like that, you’ll start to lose the ability to think for yourself and eventually lose the ability to think creatively or even remember why you are even playing music in the first place.

Miwa: I think there are already quite a few children like that. It appears to me that we need to rethink our educational approach to better align with the current generation. Some children may even feel a sense of ownership over the music by listening to it on YouTube and may not find it necessary to go through the process of starting from square one and learning to read sheet music. I believe that education is about more than learning, and the most important thing is letting students have different experiences. After all, you won't have a desire to become the real deal unless you first learn how to identify what is actually genuine.

Okuda: It's like a university entrance exam study guide saying, “Let's solve these problems in exactly the same way as the example.” The approach is clearly wrong, but that is the direction the whole world is headed. I want to tell children that this is no way to live. I want to say, “Let's go listen to something interesting,” and take them to a concert hall to hear a live performance. It would be a completely different experience, and I think it would convey many of the points you’ve touched on today. The biggest challenge in education going forward is how to expose students to a different world from the standardized, constructed world they're used to. I believe that education should provide opportunities to have extraordinary firsthand experiences.

Miwa: Instead of enjoying nature inside a video game, I feel like telling them, “Go to the seaside and try hunting for clams. You’ll have tons of fun seeing the different kinds of shells, and if you try to pick one up, a shrimp might pop out.” Experiences like those are priceless. Teaching people real joy is what education is all about.

Okuda: Today’s conversation was just as engaging as I’d expected. Thank you both for your time.

(End of Interview)

As innovators, Kaito and Ayako have something in common: the ability to sense people's energy. They are both quite open to perceiving people's energies. And I felt that this openness may be a driving force for creation. The power to sense energy, to embrace it, to feel both joy and pain. Without that, it would be impossible to create new value. I felt the gravity of Ayako's words when she said that the goal of the National Youth Orchestra of Argentina was to use art to nurture emotional intelligence as something fundamental to being human.

I also think they both agree that being a bit crazy—not just average—is what can change the world. I firmly believe that the world will change as a result of individuals like them, people who are willing to step up and take on new challenges. I was also inspired by their stories of leapfrogging and interpreting “too early” as a compliment. The fact that few people agree is partly due to our society and the current education system. By gathering the crazier among us to reshape our world, the whole of society can become more tolerant, and I think that would lead to the emergence of companies and cultures that can generate new value more easily. I was also reminded once again of how important it is to have the discipline to clear your head and embrace new values with an open mind.

(Closing statement by Okuda)

CEO of e-Education

Kaito Miwa

Born in 1986, Miwa founded the predecessor to e-Education together with Atsuyoshi Saisho while studying at Waseda University. Using video education, they supported impoverished high school students in Bangladesh who were preparing for university entrance exams, and from their first year of operations, saw many students successfully gain admission to university. After graduating from university, Miwa worked at JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) while managing e-Education’s overseas operations. He left JICA in October 2013 and became CEO of e-Education in July 2014. To date, the e-Education project has delivered support to 30,000 middle and high school students across 14 developing countries. In 2016, Miwa was selected for Forbes’ “30 Under 30 Asia” list, and in 2017, he won the first Catapult Grand Prix at ICC Fukuoka. Miwa is the author of Compassion Presentation (Hyakupāsento kyōkan purezen, Daiyamondosha, 2020).

Soprano singer President, Japan Association for Music Education Program

Ayako Tanaka

At the age of 18, Tanaka traveled to Vienna alone to study. At 22, she made her debut at the Stadttheater Bern in Switzerland, becoming the youngest soloist ever in the theater and the first Japanese person to perform there. Since then, she has performed in Vienna, London, Paris, Buenos Aires, and many other cities worldwide. Tanaka won “Best World Premiere Piece” by the Argentine Music Critic Association for her performance of Esteban Benzecry's “The 5 Cycle Songs for Coloratura Soprano and Orchestra" in Buenos Aires. The album received five stars from the BBC Music Magazine, the world's best-selling classical music magazine.

Tanaka is also engaged in giving back to society through activities such as the SCL International Youth Music Festival held in Vienna with the support of UNESCO and the Austrian government to assist young performers, as well as the National Youth Orchestra of Argentina, which was established with the support of the Argentine government to provide education to young people of various backgrounds and family situations through music.

Tanaka was named one of Newsweek's "100 Most Respected Japanese in the World" in 2019. She sang the Japanese national anthem on October 22 at the opening ceremony of the SMBC Nippon Series 2022.

Born in Kyoto, Tanaka lives and works in Vienna.

RELATED STORIES

Where the Creativity of Business Meets Art Global-Mindedness x Creativity (Part 1)

First of all, I am very honored to be able to speak with you today. But this is not the first time we’ve met.

Where the Creativity of Business Meets Art Global-Mindedness x Creativity (Part 2)

In our previous conversation, I felt that some of the keys to your global success were your decisiveness, …

Where the Creativity of Business Meets Art Second Interview: Education x Creativity (Part 1)

Today marks the first time we’re doing a three-person interview. We are joined by Mr. Kaito Miwa, CEO and co-founder of …